One Month Japanese Crash Course

I spent six months studying Japanese in preparation for a one month tour of Japan, and I can honestly say it was useful. But some things I learned were far more useful in getting around on a self-guided tour than others. Yes, knowing lots of common words and phrases helped sometimes with communicating with locals and understanding announcements and live performances, but that's not what this guide is about. You can't learn enough vocabulary in a month to help that much, and the very basics of common phrases are covered extensively elsewhere on the web. This is, instead, purely a guide to getting by reading Japanese. This is the 1% of the written language that will get you the farthest in reading signs and printed text around you everywhere in Japan.

Reading Almost Everything

In most public spaces, important information is written in plain English specifically for the accomodation of visitors. But still some 99% of text you'll encounter in Japan will be in Japanese, and there's no way you'll get anywhere close to being able to read it in the space of a month. So, the most important thing is to make sure you have a smartphone with Google Translate installed. The camera mode in that app will let you read all printed text and even some handwritten text for as long as your battery and cell service hold out--and you aren't in a space where photography is banned.

However, it's worth noting its translations are not perfect. Sometimes it gets things hilariously wrong. And it does take some time to pull out and use, so, for example, you won't be using it to read signs out the window of the bus or rapidly changing marquees. Also, it can make signs that use furigana (small characters above kanji indicating their pronunciation) unnecessarily difficult to read (the small text between lines in Google's translated image should be read as if it's on its own line in flow between the surrounding lines). Even so, it will still be your go-to method of reading Japanese text 95% of the time.

The Alphabet

English loan words are ubiquitous in Japanese text. You can hardly read a paragraph anywhere without finding at least one. The first problem is that, like most languages, the Japanese do not write nor pronounce the words it borrows from other languages the way they would be in the language they come from. They get pretty close most of the time, but certain sounds are modified to the nearest equivalent sound in Japanese.

The second problem, much more readily surmountable, is that these words are not usually written using the Latin alphabet. English loan words (by far the most common loan words) are written using a special syllabary used almost exclusively for loan words: katakana. So your absolute first must-do task is learn to read katakana reliably. With daily study, you should be able to pull this off in two weeks at most.

I recommend the app Renshuu for this purpose. It will present hiragana lessons first, but you will want to skip those. Hiragana is not going to be particularly useful in reading what you see around you in Japan. Katakana will get you far more bang for your buck. So go learn it and come back and finish this article once you've got it down.

Loan Words

Once you're comfortable with katakana, you'll want to get your eyes on as many loan words as possible to get an idea for how the Japanese tend to localize loan words. There are a few general rules that will give you the best guess at the meaning of a word you are seeing for the first time, but your best bet is to 1) learn a list of the most useful and common loan words, and 2) look at a lot of Japanese text, pick out the katakana strings, and attempt to translate them. Sometimes, it will be literally impossible to guess, for example when the word has been abbreviated. Here's a short list of common words to get you started:

- タクシー taxi

- バス bus

- スマホ smartphone

- ラメン ramen

- メニュー menu

- エレベーター elevator

- ロビー lobby

- バー bar

- レストラン restaurant

- ビール beer (not to be confused with ビル=building)

- テレビ TV

- マーケット/ market (sometimes also written マルシェ from the French)

- タバコ cigarettes, tabacco

- ドア door

But again, it's best to be prepared for anything, so here are some general rules that can help:

- More often than not, the vowel sound part of ク, ス, ル, etc. does not appear in the source word, especially when it's at the end of the word.

- ラ, リ, レ, ル, and ロ are equally likely to correspond to an "r" or "l" (along with the following vowel, if any) in the original word, so try both as you sound it out.

- Likewise, consider that バ, ビ, ブ, ベ, and ボ, while usually corresponding to a "b" sound, may occasionally replace a "v."

- Moreover, consider that ン can also be pronounced "m", particularly before a "p" sound. (e.g., キャンプ="camp")

- A chōonpu (ー) often indicates a double vowel in the source word (e.g. the "ee" in "beer") or a vowel with a following "r" (e.g. the "or" in "elevator").

- It may help to think about how certain phonemes might be pronounced in a British English accent. In most cases, it's the British English pronunciation that has been transliterated.

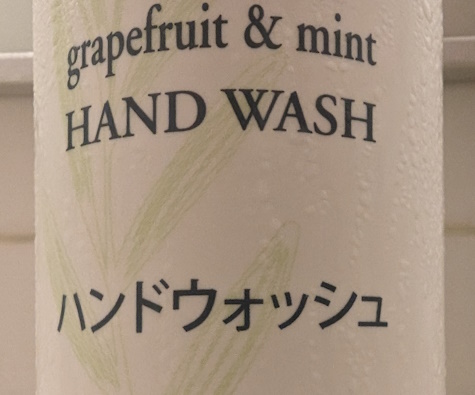

No list of rules can prepare you for everything. I never would have thought "wash" would be transliterated this way.

Also, I'd recommend learning how to write your own name, first and last, in katakana. That ability came in very handy for me on multiple occasions. Google Translate can help with this if your name is somewhat common, though the results may not be perfect. If you have an uncommon name, your best bet is to get some help from a native speaker. Listen to how they pronounce different spellings and pick the one that is most accurate. Write it down on a card and keep it in your wallet or put it in a note on your phone.

Kanji

Almost all native Japanese words, on the other hand, are not written phonetically (or at least not entirely so). They are written using Chinese ideographic characters, of which there is a vast collection. Enough that it would take years to learn them all. However, yet again, you can get a lot of mileage out of a very small subset, at least for text that conveys the most useful information for you. What follows is the subset I would recommend with pictures of them as I encountered them in the wild. I'm just documenting basic meanings here, which wildly differ depending on context anyway. And, of course, these characters can appear in a variety of words having a variety of meanings depending on context, so only the most useful meanings (in my opinion) are documented.

Numbers

Five Yen Coin

Although Arabic numerals are fairly ubiquitous in Japan, there are situations where the Chinese characters are used instead. For example, the character "5" is nowhere to be found on the above five yen coin. The numbers are these:

| Arabic | Kanji | Mnemonic |

| 1 | 一 | One line |

| 2 | 二 | Two lines |

| 3 | 三 | Three lines |

| 4 | 四 | A four-sided window (with curtains) |

| 5 | 五 | Kind of looks like a five (that's got some blur lines from how fast it's moving) |

| 6 | 六 | Six is two strokes (亠) off from eight (八). |

| 7 | 七 | Viewed upside-down, it's a 7 with a stroke through it. |

| 8 | 八 | Once upon a time it was written more like )(, with sections aimed in all four intercardinal directions. Add in the cardinal directions to make 8 total directions. |

| 9 | 九 | Looks like an "n" for "nine" |

| 10 | 十 | Looks like a "t" for "ten" |

| 100 | 百 | Looks like "100" tipped on its side |

These can be combined in straightforward ways to make arbitrary counting numbers. A guide on how to do so can be found here.

Units of Time

In Japanese, moments in time are typically described from least to most specific units. That is, the longest time units come first and the shortest last. Dates are given year first (if at all), then month, then day. Times of day are given in the usual Western order. A unit of time followed by 間 indicates that it's talking about a given length of time rather than a particular numbered time.

The unit is almost always given directly after the number. That is, the units separate the numbers. Sometimes dates are also written in MM/DD format.

Two methods of giving a date

月 means "month" or "moon". 日 means "day" or "sun". So for example, 4月17日 means the 17th of April, while 10日間 means "10 day's time."

A full date

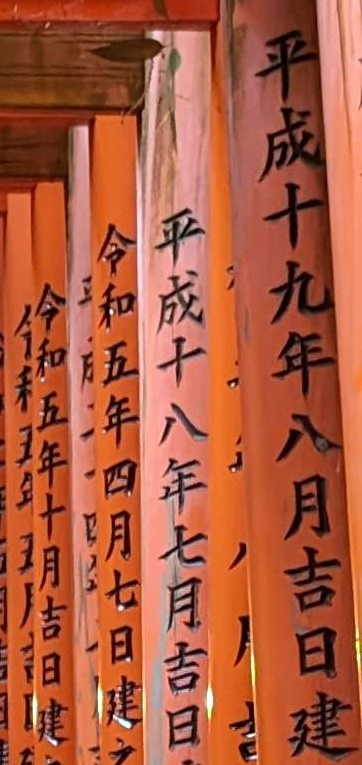

A date that includes a year may use the international year standard or it may give the year in terms of the number of years into the reign of a certain emperor. Money and the torii in the above image use the latter. In either case, it will use the character 年 to mean "year" and it will come first.

Opening Hours

Hours of the day are always given in 24-hour time, and 時 means both "hour" and "o' clock." You can remember this kanji as the sun shining on a cross planted in the ground whose shadow below it tells what hour it is.

A short span of time.

Among other things, 分 means "minute", both the period of time and the minute in a given hour. You may also see 半 ("half") to represent half past the hour. 秒 means "second," which may come up in describing the precise duration of video/audio presentations in museums. You'll notice the latter contains the 小 radical, which should remind you it's the smaller unit of time. What's that? You don't know what 小 means? My bad...

Big/Little

Toilet flush selector

大 looks like a guy spreading his arms wide to show you how BIG the fish he caught was. 小 looks like a collapsible umbrella folded up SMALL to carry. You'll want to know these especially for flush selectors like the above, which are ubiquitous. They can also be on restaurant and food stand menus describing portion size (though you'll presumably be using Translate on those). In this context, you may also see a 並 option ("normal" size). Occasionally, you might see 半 as well for a very small (half-sized) portion.

Open/Close

Elevator Buttons

These two characters are very similar. Both depict a gate 門 with something under it. 開 looks like a picnic table with open seats for you. 閉 looks like a security guard spreading his arms to let you know the area is closed. The most common place to see these symbols are on elevator buttons, as above. As Japanese elevators seem to stay open longer before closing automatically by default, you will absolutely want to be able to use these buttons.

Yen

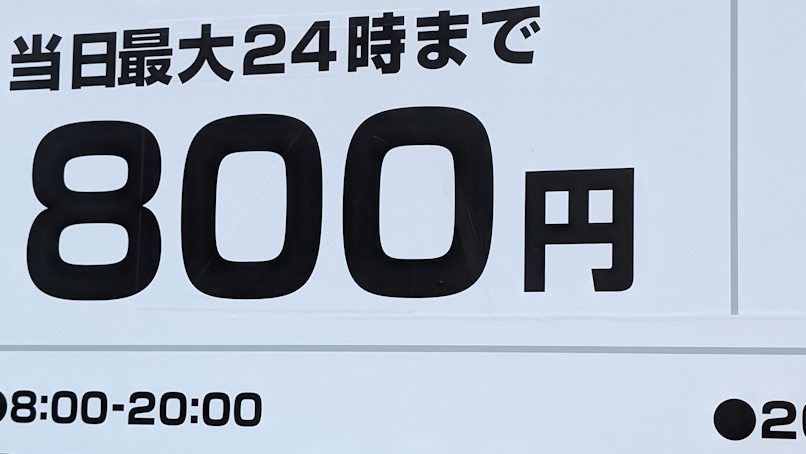

800 yen

Although the international symbol for the JPY currency is ¥, in Japan, it's more commonly represented by the character 円. It's usually found immediately after a number (Arabic or Kanji).

Push/Pull

Push

Pull

Want to interact with doors and windows without looking like an idiot? 押 looks like an skeleton's stubby five-fingered hand about to PUSH a pressure plate. 引 looks like bow and a bow string that has been PULLed tight.

A 20% discount on prepared food an hour before the grocery store closes.

引 can also be used to mean a discounted price. Think of it as the price being PULLed down. It can be used on a label like 200円引 (200 yen flat discount) or a percent discount as above (割 means a tenth of something).

Male/Female

The only time this is likely to come up is onsen changing rooms, but it's worth knowing that 男 means male and 女 means female. The latter vaguely resembles a woman with narrow waist and large bust perhaps? Most of the time gendered toilets are labeled using the commonly recognized symbols or English words.

Before/After

Before/in front of is 前 while after/behind is 後. You'll see the former constantly in all kinds of contexts. Before a certain time (午前 = before noon vs. 午後 = afternoon). In front of a certain place (駅前 = in front of the train station). Even your name that comes before, i.e. your given name (名前).

Train Station

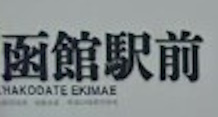

A tram stop in front of Hakodate Train Station

駅 means train station. This is a word you'll also often see in Latin spelling as "eki." If you squint a little, it kind of looks like the letters "JR" as in "Japan Rail", so maybe that will help you recognize it.

Entrance/Exit

An exit sign

Although entrances and exits are labeled in English and with symbols in the majority of cases, sometimes less touristy properties in less touristy areas do not bother with the translation. Both entrance and exit are spelled with the character 口 (meaning "mouth" or, as in this case, "opening"). Entrance is 入口, wherein 入 means "put in/insert." You can imagine it to be a thread (left) being inserted into the eye of a needle (right). Exit is 出口, wherein 出 means "go out." You can imagine it is a small house plant growing OUT from a pot.

Days of the Week

Water

Every day of the week is associated with a concrete common noun rather than, in Western languages, some Greek or Norse deity. So, for instance, "Monday" would be 月曜日, lit. "moon day of the week". But since they all end in 曜日, this part is often omitted on signs and calendars, the same way we might abbreviate "Monday" to "Mon.". Google Translate will then, not having any context, give you some random word that seems to be unrelated to a day at all, so it's useful to know what noun represents each day:

| Day | Kanji | Meaning |

| Sunday | 日 | Sun |

| Monday | 月 | Moon |

| Tuesday | 火 | Fire |

| Wednesday | 水 | Water |

| Thursday | 木 | Wood |

| Friday | 金 | Gold |

| Saturday | 土 | Soil |

Random bonus kanji (optional)

Esan Azalea Park

No promises these will be of any use—feel free to skip this section if you don't have time—but I did occasionally use them in navigation.

人 means person. 公 means, among other things, "public", so you may see it on government properties, or, for example, on a 公園 (public park).

山 means mountain. There are a lot of mountains in Japan and you can use them to navigate by sometimes. Sometimes they are in parks. So, for instance, Maruyama Park in Sapporo is named solely using kanji already mentioned: 円山公園. (Here, 円 is being used to mean "circle"--coins are circular too, you may notice).

道 means "road". 交差点 means "intersection". 車 means "car". 建物 means "building". 方 might mean "direction", i.e. if a sign is telling you what direction to go for some destination. 空港 means "airport." (港 by itself means "port" or "harbor" e.g. クルーズ港="cruise port".)

日本 means "Japan." 東京 means "Tokyo." 京都 means "Kyoto." 大阪 means "Osaka." 外国 means "foreign country". So a Japanese person is 日本人, and everyone else is 外国人, or even just 外人.

自 means "self", for instance in the pronoun 自分="myself/yourself/oneself". But you're more likely to see it in the context of automatic things ("auto" is Greek for "self" you see), such as in the phrase 自動ドア ("automatic door").

Other tips

Try to review and quiz yourself on all these characters in a variety of fonts. The same character can look wildly different in different font faces, and especially in handwriting. Renshuu has the ability to display quizzes in a different font face every day from a pool of 7 or 8 different options, but this is only a feature in the pro version, so consider buying a month of that.

Try cruising around the streets of Tokyo on Google Street View and seeing how many of the signs you see have Katakana text you can translate or characters you recognize. This will also expose you to a wide variety of ways of drawing the same characters.

To write in Japanese, try installing a keyboard on your phone that can automatically translate text as you type it, like Desh Keyboard. At the very least, if the situation calls for it, such as searches for locations on Google Maps and providing the pronunciation of your name when registering on Japanese websites, it will speed up the process of typing out katakana. It will also make it easier to draw kanji you see in order to use them when you can't copy/paste them (for instance, when Google Translate fails to recognize them as text.)